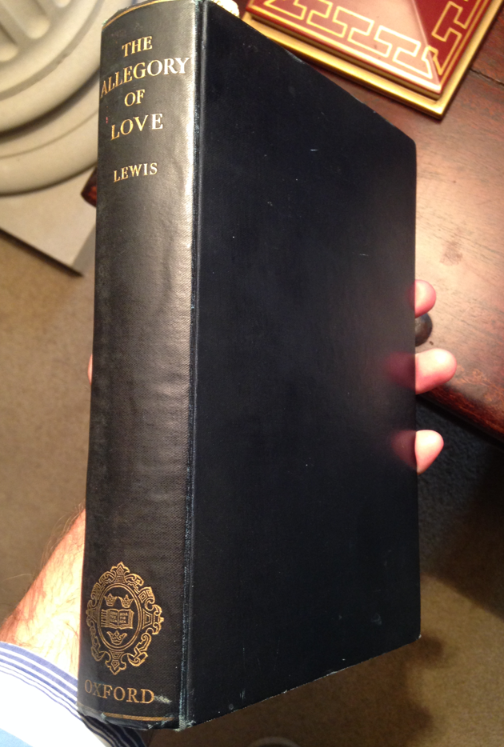

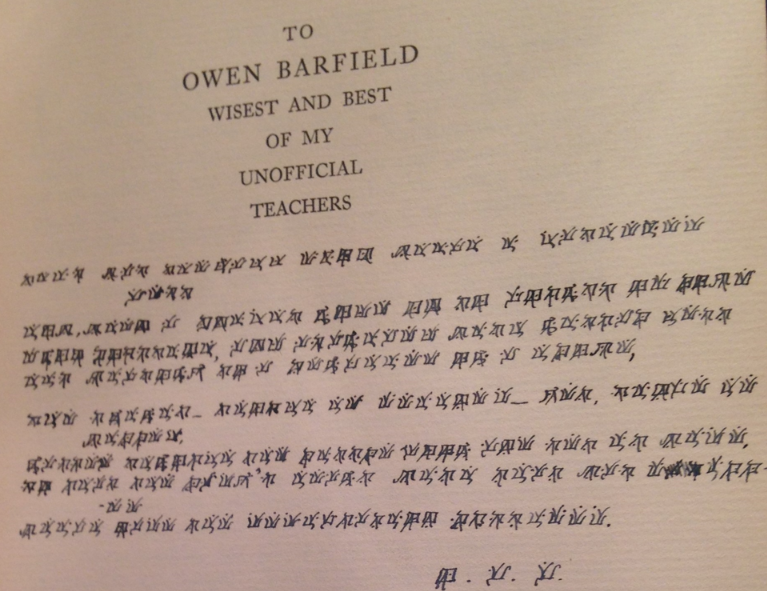

Among the invaluable Inklings books and memorabilia shown to me by Walter Hooper during my visit to his flat on July 22, 2015 was a first edition copy of The Allegory of Love (1936), C.S. Lewis’s own presentation copy to Owen Barfield, later given to Walter by Owen. What made it so interesting was not just its provenance, but more so its inscription on the dedication page encoded in a runic cipher.

Late last winter, nearing the end of my personal quest to collect and read everything by Lewis, I decided to buckle down and solve it. But I didn’t do it alone. My wife Rachael, who is more experienced in word puzzles and cryptography, suggested we start by finding a “key”–some letter(s) we were certain of, giving us at least a few symbol-letter correlations to work with. Assuming this was a simple substitution cipher, we could start by filling in the key letters wherever we found the same symbols, and then try to work out the less frequent, and therefore more difficult ones. I pointed out that Lewis would sometimes end his letters with his initials: “C. S. L.,” giving us three common consonants right off the bat to fill in. She started hunting for single-letter words, knowing they would be vowels (either “A” or “I”), for double letters (“TT,” “LL,” “SS,” “OO,” for example), and for the most common short words, such as articles or prepositions.

Several days later, working on it in the evenings as time and our children allowed, we were still stuck. Taking “C. S. L.” as a fixed point, we couldn’t make sense of the cipher. Words were not often snapping into place, and only occasionally would they make contextual sense. I began to wonder if the note was even written in English at all. Knowing Lewis’s and Barfield’s facility with languages, I started researching Old English and even Old Norse words that seemed to fit the letter patterns we were finding, but without luck.

Eventually I decided to start over. We’d print out two more copies, and use a different method for each. One would be a fresh start with the old key: “C. S. L.” The other would use a different key, a discovery of Rachael’s: the most common word, appearing five times, was almost certainly the definite article (“the”). We would be scrupulous about putting down only what was consistent with each of those keys.

The old key again proved fruitless, and at some point was abandoned. The second key started to yield more results, but it still wasn’t enough. The words we were on the cusp of decoding must not have been common, or weren’t part of any well-known phrases or quotations, since we could not with any confidence intuitively solve it as if it were a partially-filled-in “Wheel of Fortune” puzzle. But at least they were consistent with English spelling and usage.

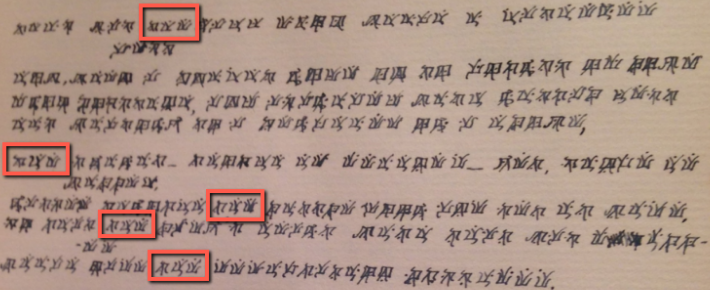

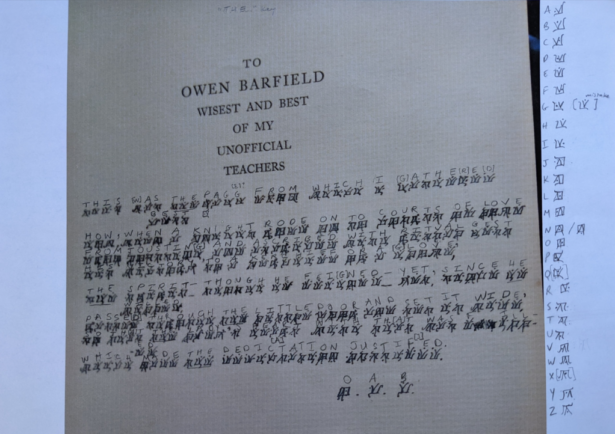

The real breakthrough came when Rachael realized that there was a pattern to the substitution cipher. Or rather, to the creation of the cipher. That the symbols were hard to distinguish, we already knew. They were all variations of an all-too-similar visual pattern with three distinct elements: a partially open or closed square, inscribed with a 45-degree angle (like a “V”) opened to one of the four cardinal directions, with a dot placed somewhere in the complete shape. What dawned on her was that the variations of this pattern made sense when put in alphabetical order. Groups of letters (A, B, C; D, E, F; G, H, I, and so on) would share the same exact outer box shape and inner “V” rotation, the only difference being the precise placement of the dot. Using this knowledge, we were able to confirm symbols we were unsure of because of the poor picture quality, and even theorize letters that we could not inductively identify from the text at all (since they did not appear), such as “Q” and “X.”

We had struck gold. Everything came together in a rush. Words came to life on the page; we mapped out the full alphabet; the kids asked us for bedtime snacks in vain as we enthusiastically pointed out and marked down all the letter-solutions, even finding some spelling mistakes in the text itself. It was only at this point that I realized that my basic assumption about the code had been totally mistaken. This note was not signed by C. S. L. at all; it was by one “O. A. B.”, invented, composed, and written, in fact, by Owen Arthur Barfield.

That physical copy of The Allegory of Love may have been Lewis’s presentation copy to Barfield, but the cipher was written to Walter, from Owen, about Lewis. I cannot at this distance of time recall whether Walter had told me all this to begin with. But somehow, between deciding to decode it and originally seeing the cipher on the dedication page six and a half years earlier, I had fundamentally mistaken the nature of the text. It wasn’t a sly note from Lewis to Barfield, written in a code perhaps known only to themselves. It was, in fact, a graciously humble poem about Lewis’s dedication of The Allegory of Love to Barfield by Barfield himself, adding another layer of interest to the book’s publication history:

This was the page from which I gathered best

How, when a knight rode on to courts of love

From jousting and ascribed with ritual gest

His victory to a kerchief or a glove,

The spirit–though he feigned–yet, since he willed,

Passed through the little door and set it wide,

So that the lady’s heart with that was filled

Which made the dedication justified.

O. A. B.