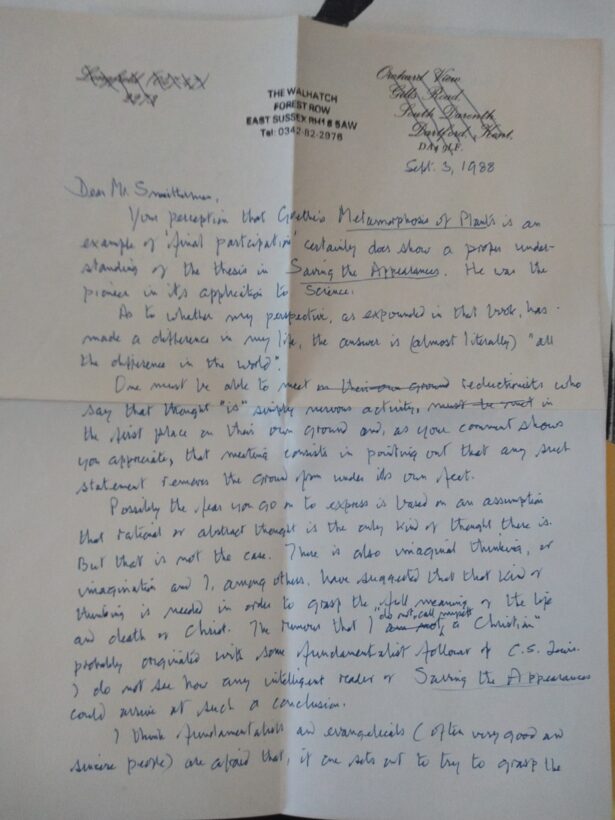

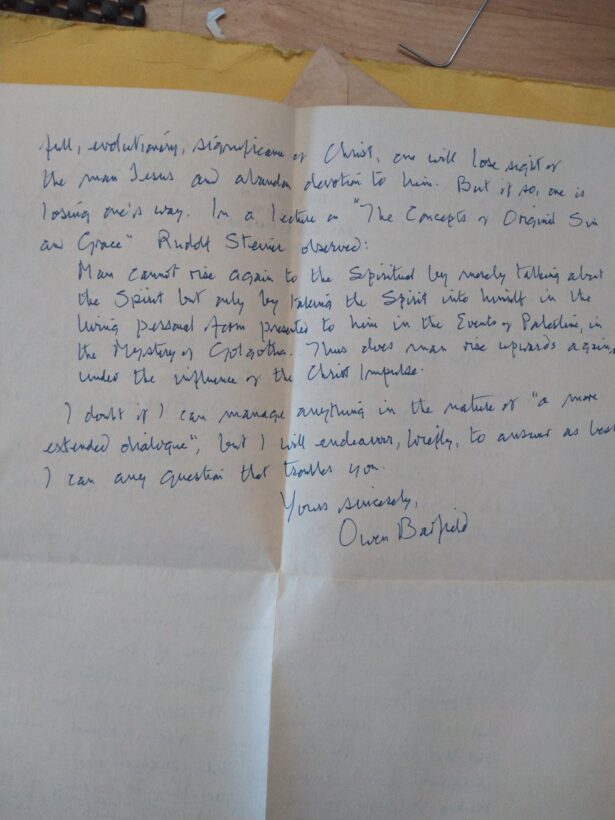

Sharing my correspondence with Owen Barfield is a gift that I’m honored to bestow. Beginning in 1988 – when he was 90 years old – we traded letters until 1995, two years before he passed. He sent copies of essays and talks of his, and commented on poems and essays I sent to him. He recommended books to read. I told him of authors I’d found. All told, I have sixteen letters from him.

Sharing my correspondence is also humbling. It does involve two people, after all, and only makes full sense when both people are taken into account. At the very least, that means including the text of my letters to Barfield, as I have them – eleven photocopies of handwritten letters, and one handwritten rough draft.

I’m not the sharpest tack in the toolbox, and that fact is on full display in my letters. I hold tenaciously to seemingly arbitrary, sometimes specious notions. I insist on sharing personal, even intimate, details of my life. But Barfield’s letters don’t make much sense unless we know the other half of the conversation. In fact, I know only as much about Barfield as any student of his does, but I know lots more about myself, some of which might make his letters more real.

If you want to read more about the context of my writing to him, help yourself to the last section. What I’ll do first is focus on Owen Barfield, as I saw him at the time of writing the letters, as best I can recollect, from memory, journals, email, and any other sources I have at hand.1

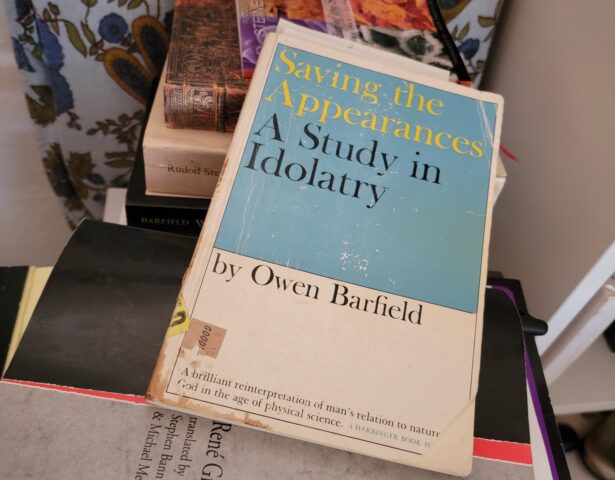

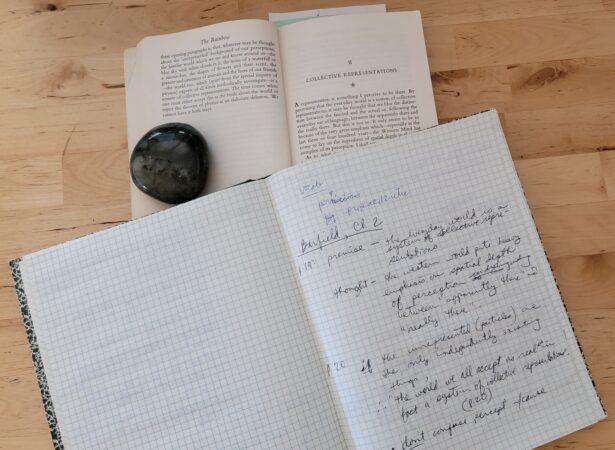

It was Saving the Appearances that started it all, and it was “The Rainbow” chapter that really hit me. This was my first encounter with any serious philosophical writing, even though this text itself is as literary as it is argumentative. So I had to read slowly. The chapters in the book are gloriously, graciously short, and I could better digest the smaller chunks.

The question, ‘what is real, really?’ is what captured my thinking. First, just by asking that question of myself, I felt a loosening, a tiny play of space between me and ‘the real’. Just by engaging thoughtfully and deliberately with the text, I found I was looking at everything a little bit differently.

Second, I latched on to his statements that solidity is possibly the Primary Attribute, in contemporary consciousness, of reality, but that when you think things through carefully, you see that almost never do we actually experience the solidity that we presume as the necessary, and most obvious, feature – and proof – of reality.

Third, his focus on modern science – it’s methods and principles – really caught my interest, since I was, at the time of the first letters, a high school science teacher who loved science and the history of science, and was curious about quantum mechanics.

What Barfield then discusses in “Collective Representations” was an entirely new concept to me. I had a bachelor’s degree in Education, was very curious, and read a lot, but only post-university did I broaden my reading, and deepen my thinking. I wasn’t very successful following his argument, from premise to premise (which word I wouldn’t even have used then) and through to conclusion, which in turn was the premise of a new argument.

What I did get was another subtle detachment from my view of what was real. Imagine, Barfield writes, if everyone around you, anyone you might talk to, believed in, and claimed to see, divine spirits animating trees. Imagine there were no contradicting sources. Either this is mass hysteria, or there’s something to what those people experience. Only when there does come a contradiction – and we know those came, because we are the result – can they even formulate such a thing. Clearly, what is real, and what all people think is real, are associated, somehow.

Beyond philosophy of science and ontology, I was, at the time, actually as much or more concerned with the religious, moral, and psychological implications of Barfield’s thought. My second letter (Aug. 20, 1988) lays it out:

What about the similarity between your comments about a new consciousness, on the one hand, and what we here in the States have come to call the New Age movement on the other hand, the latter having unmistakable demonic elements?

This last point brings to mind a recent dilemma I find developing in me: what if the arguments I employ in refuting what I believe to be “bad elements” of modern science also bring into question aspects of my own faith in Christ? Or, in other words, I fear that some of my rashly expressed (and incompletely thought through) ideas and arguments, against both science and demonic elements of the “occult” may come back to “haunt” my own belief in God.

I wasn’t, nor am, a theologian, and very naïve, too. Intellectually, philosophically, his work became my reading list and commentary. What I learned from him, from his work, was my map through the world of thought, and through the philosophical canon at an American university where I studied in the MA program in Philosophy. My study of Barfield and my study of philosophy unfolded together. Too closely, according to my thesis committee: they argued that I hadn’t achieved a critical distance from Barfield’s thought, which was serious enough for them to reject my thesis entirely, and fail me out of the program as a result.

But I had learned what I wanted to learn: I read medieval philosophy, philosophy of language, American pragmatism, eco-philosophy, feminist philosophy, and logic from some very good scholars. I studied Latin from a delightfully brilliant professor in the Classics department, theology from a young, sober, smart instructor in the Religious Studies department, and Kant from an intense semester with a quiet, kind, deep-thinking Kant scholar.

And I read Barfield: Saving the Appearances, Worlds Apart, The Rediscovery of Meaning, Poetic Diction, History in English Words, and various essays. And re-read them.

And then I read works mentioned by Barfield, or that mentioned Barfield, especially anyone trying to extend Barfield’s seminal thinking, or develop it in new ways.

So in the course of our correspondence, I became more focused on everything I was learning as a graduate student, and could then ask different questions, and ask them in different ways. I queried Barfield on his basic terminology of ‘unrepresented’, ‘figuration’, ‘original participation’, ‘idolatry’, and ‘final participation’; I pushed him on questions of praxis: how do you consciously participate? How does metaphor work to change one’s thinking? What is the world really like ‘bathed in the light of final participation’?

I should point out that the correspondence itself was not the only time I thought about Barfield’s work. The text of my letters are only a few thousand words; my thesis unraveling Saving the Appearances was over 25,000 words. The thesis, in turn, was a distillation of all my reading and writing and thinking and journaling about Barfield’s work.

But it was science we talked about the most. The word itself occurs 36 times (Saving the Appearances occurs 26 times; philosophy occurs 17 times; Steiner, 8). It was not only the laboratory practice of science and its method, but the scientistic character of contemporary thinking – on the level relevant to the evolutionary scheme Barfield lays out – that most concerned me. Scientism constricted me, and Barfield offered a way out.

One of my first semesters of graduate school, in 1989 sometime, I took a History of Science course. It was a graduate level course, taught by a very demanding professor. The first paper I wrote, she insisted I rewrite it, asking me, “Why are you so angry?” I did rewrite it, in a more detached way, but it wasn’t easy.

A year or so later, in a graduate seminar “Challenges to Authoritarian Science”, I read in class a poem I’d written that was an exercise in understanding conscious figuration, a la Saving the Appearances. One of the first conference papers I read as a graduate student was actually not at a Philosophy conference, but a conference of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, where I read a paper on Paul Feyerabend’s Against Method that was heavily indebted to my reading Barfield, and made it as part of the chapter in my thesis titled “Science, History and Sensibility.”

Modern science was the villain, and Barfield was my knight in shining armor.

Even while Owen Barfield was still with us in the waking world, I knew my work, my study of his thought, was going to proceed without his help, his direction, his comment. Like I said, he was already 90 years old when we started our letter exchange. The last several years of his life, we didn’t even exchange letters. I didn’t learn of his death until quite some time after the fact.

Since 1997, the year Owen Barfield passed on – as did my father, just three days after Owen passed – I’ve read closely as much of his work as I can. Even in the last several years, thirty years on, I’m still finding new essays, poems, stories, and I’m still humbled by his great intellect, and my struggles to understand him.

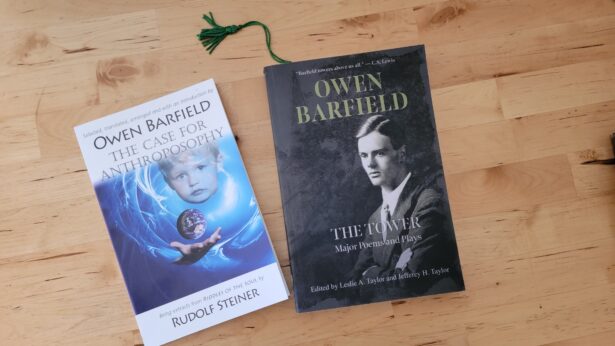

Just in the last year I’ve discovered lots of new material, by and about Barfield, including these two gems: The Case for Anthroposophy, and The Tower.

Sending his letters to the Wade Center at Wheaton College is an exercise in humility, an occasion for many many memories, and sadness that so much has passed. Thankfully for me, this release and letting go coincides with, and is partly prompted by, connections with many new friends of Barfield, finding new writings of his to study closely, new intellectual and spiritual questions and goals to ask and achieve.

My hope is that this correspondence will hearten and encourage others, not only in their study of Owen Barfield’s wonderful mind and thought, but also to keep asking questions, and to connect with other mentors and teachers, like I did, over forty years ago.

Back in 1988, when I first wrote to Owen Barfield, and heard back from him within two weeks or so, there was no internet. Cellphones didn’t exist. Amazon didn’t exist. Nor did I imagine they would.

Airmail existed.

I wrote to Barfield because I’d read Saving the Appearances, and it changed my thinking. I’d never read anything like it.

I had a bachelor’s degree in Secondary (high school level) English and Physical Science. I was a certified high school Science and English teacher. My first, and only, full-time teaching position lasted two years, and was coming to an end by the time I wrote that first letter in 1988.

That teaching gig started in the fall of 1986, at a very small private Christian school in Austin, Texas, a year after I’d graduated from the University of Texas – Austin. The school hired me to teach the entire high school science curriculum – Earth Science, Physical Science, Biology, and Chemistry (as well as PE and Health!). I had about a month to prepare before the first day of class, and part of my preparation was to find appropriate textbooks for each of the classes.

As I reviewed multiple textbook candidates, I read through many introductory chapters that rehearsed the ‘history of science’ up to that point. A stock story took shape through all those different renderings: First there was superstition, and spontaneous generation. Then Galileo. Then experimentation, Pasteur, Maxwell, Edison. And so truth about the world dawned and shone bright.

By the time I read the fourth or fifth rendition, though, I suspected the story was incomplete, and I dove into my own studies: biographies of Lavoisier and other early scientists including Pasteur, Maxwell, Darwin and Edison; and current critiques of modern science, like David Ehrenfeld’s The Arrogance of Humanism. And Daniel Boorstin’s The Discoverers.

So I began teaching science.

I immersed myself in science itself, of course, and thoroughly enjoyed not only teaching, but the learning too: experimental design, controls, the law of dominance and recession. I required all my students to learn – by practice – the scientific method: hypothesis, experimentation, conclusions. They kept lab notebooks. They watched the night sky several nights a week for a month to watch the rising of the moon and stars. They observed a solar eclipse through homemade light boxes. We looked through my own telescope at planets, the moon, and stars.

We mapped out small grids of outside lawn, and catalogued what we could discern as separate species of grass and plants. We attended lectures together at the University of Texas, given by renowned scientists. We went to the zoo, noting on paper the different species and their relationships to one another.

Still, the history of science continued to nag me, in my own studies. Were all humans before Galileo really so superstitious? Really so stupid?

At this same time, and long before, I considered myself a CS Lewis acolyte. I read all his most popular works, and then some. Miracles and The Problem of Pain were the first, closest writings to philosophical work that I’d read, and I loved the argumentation and dialectic.

I also knew of Lewis’ references to his friend Owen Barfield, and Barfield’s book Poetic Diction, and I was deeply intrigued. Again, this was before the internet and Amazon. I haunted Half Price Books all over Austin, and every local independent bookstore, routinely already, and always kept an eye out for Poetic Diction.

While in one of those stores, I ran into a friend who was also a high school science teacher, from a different school. He knew of Poetic Diction, but the book he strongly recommended I read first was Barfield’s Saving the Appearances.

One day he and I and a third teacher friend all three met to discuss the history of science, Lewis, Barfield, and Saving the Appearances. As I remember, as we sat, the first thing they said, as a lead-in to Barfield, was, “You have to read Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason.” I had no clue who Kant was. They loaned me a copy of CoPR, as well as a copy of StheA.

Of course, I couldn’t make heads nor tails of CoPR, but that was my first taste of one of the central texts in the academic philosophical canon. StheA, on the other hand, changed me from the moment I made it through the first few chapters. This was in 1987.

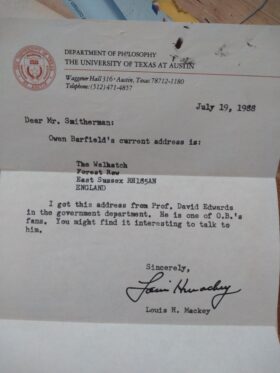

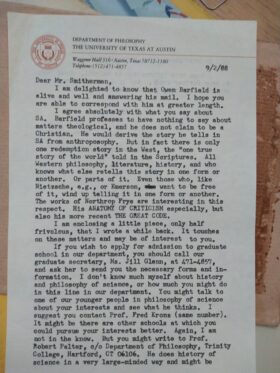

By the next year, I had finished reading StheA, reread it, and tracked down Owen Barfield’s address. Getting his address took serious sleuthing, and meetings with two different UT professors to even first establish that Barfield was still alive! I wrote Barfield in 1988, and heard back from him about two weeks later.

He wrote his letter on the old, onion skin, fold-up airmail paper, and when I pulled it from the mailbox, it was like getting a letter from the past. In fact, more like getting a letter from CS Lewis than from Barfield himself, since at that time I was much more thoroughly at home and familiar with Lewis (and Tolkien) than I was with Barfield.

Within a year of that first exchange of letters, I had taken my first college level Philosophy class, been accepted into graduate programs at the University of Texas and the University of Montana, and chosen Montana to study for an MA, with intentions to focus on the history and philosophy of science, with an emphasis on and reference to Owen Barfield’s Saving the Appearances.

Between 1988 and 1995, Owen Barfield wrote 15 letters to me, always in reply to a letter from me. I asked him many, many questions, about the evolution of consciousness, the Gospels, himself. My initial, predominant concerns and interests, in fact, were as much spiritual and religious as philosophical and scientific. The overall general consequence, though, was that my life was forever changed.

I’ve already mentioned my going to graduate school, not just inspired by reading his work, but in order to study his work. I took classes on medieval philosophy, Latin, and the history of science so that I could understand those topics, and Barfield, better. His work gave me a solid orientation in which to engage those other topics and disciplines.

And his work led me to Rudolf Steiner’s work. That’s another, entire, lifelong chain of events, which I won’t go into here, but indicates the depths to which Owen Barfield affected me.

His letters to me, in total, amount to less than 5,000 words. But the personal, living connection with him, punctuating the hours and hours and hours of reading every work of his I could lay my hands on, profoundly affected me.

Thirty-four years later, I’ve read most of his published work. I presented my own understanding of his work at academic conferences. I published my master’s thesis titled Philosophy and the Evolution of Consciousness: Owen Barfield’s Saving the Appearances. I am a grateful, honored founding member of the Owen Barfield Society. I’ve written stories, poems, essays and scribbles dealing with and coming to grips with his work. I’ve talked countless hours to countless people about his work. I’ve read countless books, journal articles, and blog posts about his work.

I say all this, because the more I’ve learned about his life, and the broader I make my own, the better I understand his writings. By ‘broader’ I mean new practices. By ‘understand’ I refer to shared practices that also share effects. Researching etymologies, and meditating on what I find. Writing a poem in an attempt to capture a glimpse of newness, to outline a felt change of consciousness.

That’s what a method is meant to do: two people, following the same method, can achieve similar results, without ever having contact with, or even knowledge of, one another. If they do encounter one another, there will be recognition in the language they use.

Missoula, Montana. Walked this trail hundreds of times, with the dog, by myself, with family and friends. For a long stretch – 6 years? – every walk probably had me thinking about the evolution of consciousness.

Back to the letters.

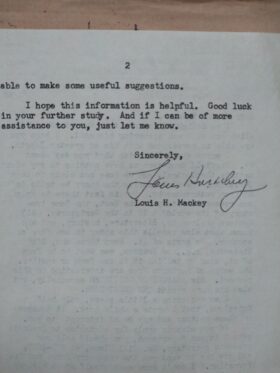

The content itself of his letters to me hold interest for others of his students, of course, and so I’ve donated them all to the Wheaton College Wade Center Owen Barfield archive, for others to share with me what I learned from him. But those letters speak as much of me as of him, for better or worse. He answered my questions, and attempted to make sense to me.

Also, he made clear to me that, given my first letter reached him in his 90th year, he had less and less energy, time and mental presence with which to give to his replies. I am forever grateful for every ounce of energy, every moment of attention that he did share with me.

The letters cover 1988 to 1995, with a gap between 1992 and 1995. I graduated from UT in 1983. I taught high school science from 1986 to 1988. I went to grad school in the fall of 1989 in Missoula, Montana. I studied philosophy from 1989 to 1996, and wrote the essays that would make up my submitted (never approved) thesis.2

During the years of our letters, I was deeply absorbed in strong and complicating impulses: newly married, raising a child, studying philosophy, working, participating in a Christian church and community. These are always behind the scenes, and occasionally make cameo appearances in a letter. Weaved into and through it all, was Barfield.

Living in Missoula, Montana afforded me lots of time outside, in the trees, listening to the river or creek, watching the sun and moon rise and set. Studying at the University of Montana afforded me lots of opportunities to think about time outside, in the trees, listening to the river or creek, watching the sun and moon rise and set. Deep ecology, feminist philosophy, critique of science, environmental policy, all were subjects of classes, conversations, get togethers, presentations. It was an exciting time in my life.

Even with my grad student colleagues, I became know as the Barfield guy. One day, a fellow student told me she’d come across a book in the library – there was no internet at that time! – in which the author discusses Owen Barfield, and maybe I would be interested? I thanked her, and rushed to the library to check out The Reenchantment of the World by Morris Berman. I would come to treasure my own copy of that book, and traded two letters with Morris Berman, in which he mentioned his meeting Barfield, and even asked me to ask Owen if he’d read Berman’s new book, Coming to Our Senses: Body and Spirit in the Hidden History of the West.

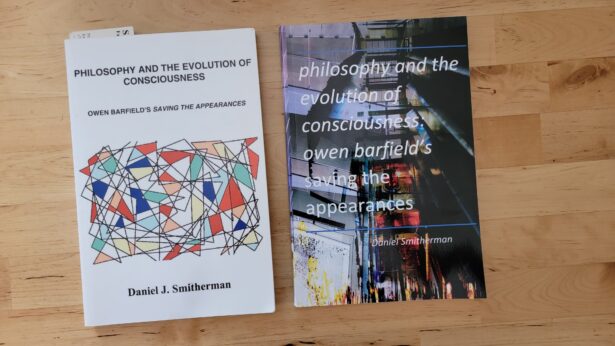

Original and 2nd version of my self-published thesis, Philosophy and the Evolution of Consciousness: Owen Barfield’s Saving the Appearances.

By the time I’d left grad school, and self-published what was my master’s thesis, I was head-down into a career in software (having found no prospects in academia). From 1997 to 2015, I went from software customer support, to software implementation, data quality, testing, database application development, and even technical writing.

All through that time, right up to 2022, I’ve read, studied, meditated on, written about, and presented in person on Owen Barfield’s thought and writings. Through that time, I’ve changed and grown (I hope!). My views and understanding have changed. Just a few days ago, I read a post of mine on my blog Save the Phenomena, where I wrote:

“the work of both Barfield and Steiner is much more about phenomenology than it is about spiritual practices – though they both use the term ‘spirit’ in their writings. I think that is why, even with Steiner’s immense written library of work, and his genius and vision, he – and his creation Anthroposophy – are not nearly as well known as, for instance, Madame Blavatsky and Theosophy. Barfield and Steiner are simply not very accessible, and their bias in favor of the intellect – a thoroughly considered, explicit and articulated bias, but a bias nonetheless – strengthens that sense of inaccessibility.”

I’m shocked that I wrote that their work “is much more about phenomenology than it is about spiritual practices”! Did I not understand, in 2009, that phenomenology is spiritual practice, as Steiner knew full well and why he so often referenced his books Truth and Knowledge and Philosophy of Freedom?

But that just means I’m still learning. May that blessing be yours too.

1 I have several personal journals covering the time we corresponded, including the very first notes I made as I read Saving the Appearances. Return.

2 I’d submitted a first draft of my thesis in 1992, a study of Saving the Appearances, applied to the history of major figures in the philosophical canon as I understood it. My committee required changes. I wrote several new drafts, but the committee declined to sign off on that thesis. The department officially dropped me from the program in 1996. I appealed, twice, without satisfaction. I self-published my thesis in 2000. Return.